A Conversation, a Seed Planted, and a Life Saved

Impact Report, March 2025

In this Impact Report, our newest intern Alora Tunstill (Northwest Arkansas) shares one of her favorite conversation stories. She underscores how important it is to engage those around us in conversation about important topics like abortion, lifestyle choices, and spiritual things.

Our mission is to help you to learn the same conversation skills Alora discusses in this letter, and to help you teach others around you in your church and community. See jfaweb.org/calendar for upcoming workshops, both in your community and online anywhere in the world. Thank you for partnering with JFA through financial support and prayer as we seek to reach more people.

-Steve Wagner, Executive Director

My mom, Rachael, grew up in a lukewarm Christian home only going to church on holidays like Easter and Christmas. She had a basic understanding of who God is. She knew she was a sinner and that if she died she would be forever separated from God.

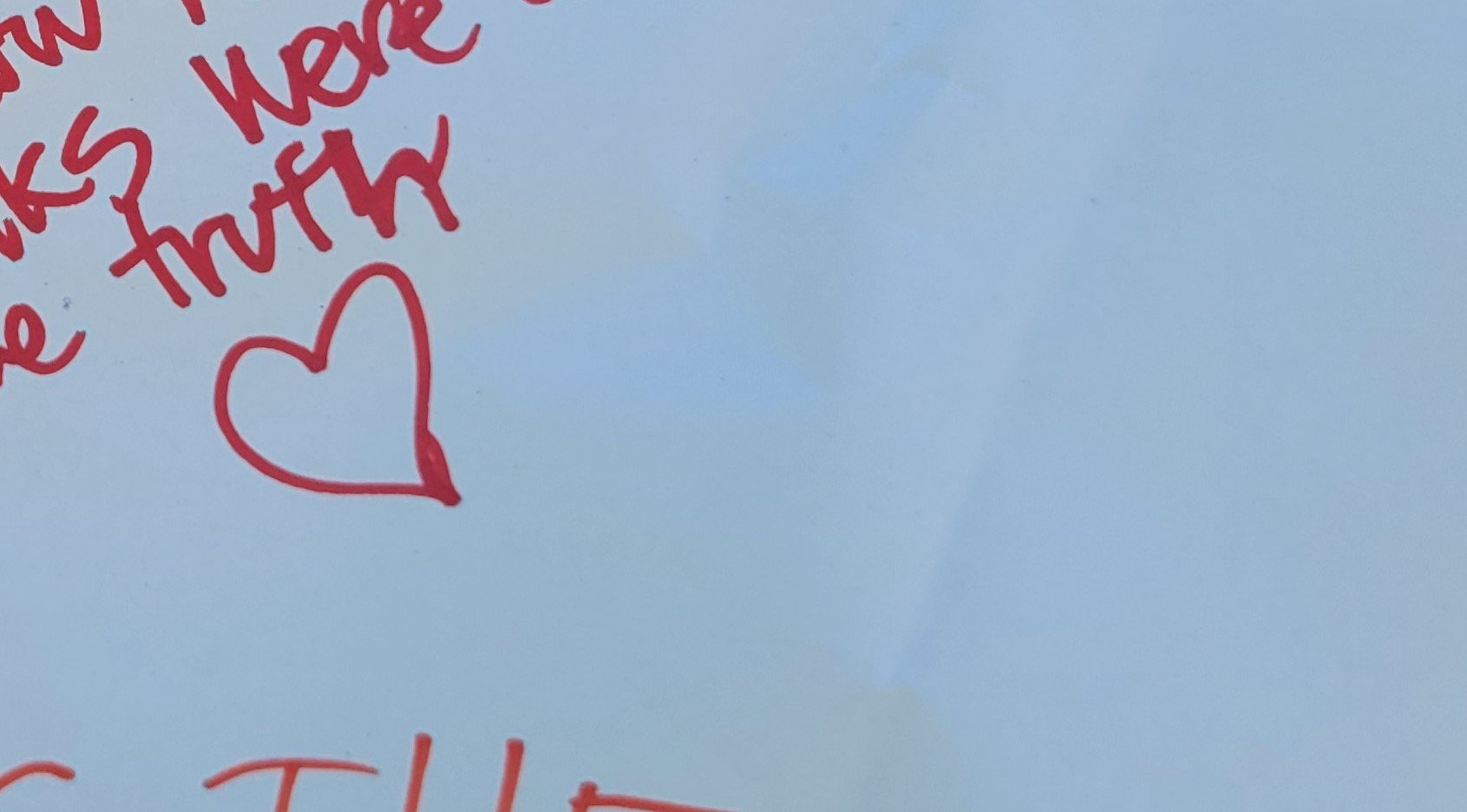

Huntsville Pregnancy Resource Center made an eight-minute video of Rachael (right) and Alora (left) sharing this story. Watch the video here.

Her parents divorced when she was three years old. She didn’t have a real relationship with her siblings; her friends were her priority. During high school she often spent her time with the wrong influences.

She got a job working at a small barbecue restaurant when she was in 10th grade. It was here she met my dad, Nicholas. He was a country boy who had no spiritual knowledge. They started dating, partying, and drinking together. Their lives revolved around themselves.

My dad’s family unit was also a wreck. His dad was an alcoholic, and his mom was completely uninvolved. He lived with his great-grandparents, and some of his aunts and uncles took an interest in him.

Shortly after my mom graduated from high school, she moved in with some friends and began using drugs. She continued to work at the restaurant but also got a job at a dental office. Three of her co-workers began speaking to her about making good choices with her life. Her aunt also took time to encourage her and share truth with her. My mom felt safe to open up to her co-workers and her aunt because they took the time to start conversations with her about hard things and remained her friends even when they disagreed. They found common ground with her through everyday conversations. They accepted her for who she was. They challenged her with truth by their own right living.

Around this time, my mom discovered that she was pregnant and that she was already five months along. She was only 19. She was still using drugs and still dating my dad, but they weren’t married, and she felt alone. She felt the only option she had was an abortion.

Since she was so far along, the procedure would take two days. The first day the doctor would implant laminaria which is used in the dilation and evacuation abortion procedure. The next day she would go in for the surgical part of the procedure. The clinic was cold, unwelcoming, and lonely.

After the implant was finished, they did an ultrasound, and she saw her baby and heard the heartbeat. Suddenly she realized she couldn’t go through with the procedure. She felt God calling out to her, asking her to stop running and surrender to Him. She gave her life to Him right there and left the clinic.

Because her Christian friends at the dental office had taken the time to talk with her, listen to her, and challenge her toward truth, she knew she could call them and that they would help her.

(Above) Alora and her parents enjoy the snow when Alora was just four months old. (Below) Alora and her mom pause for a recent photo. Alora is now serving as an intern with JFA in Northwest Arkansas and raising support to serve as a Training Specialist. Learn more about her work here.

Through the scramble of trying to figure out what to do next, my parents made some phone calls to several OB-GYN doctors. No one wanted to take her as a patient since the abortion procedure had already been started. Her co-workers, however, knew of a local pregnancy resource center close by, and they decided to see if they could get care there. They went in looking for help and love.

The Huntsville Pregnancy Resource Center (huntsvilleprc.org) immediately called a doctor who was willing to help. The doctor didn’t promise that he could save their baby, but he said he would do what he could. He removed the laminaria that the abortion clinic had implanted. Everyone held their breath and prayed. They did an ultrasound and there was a heartbeat! What a miracle!

Shortly afterward, my dad gave his life to the Lord, and my parents got married. Four months later their baby was born – me! I was born with no health issues or side effects from the drugs or from the first step of the abortion procedure.

What can a conversation change? Turns out it can save a life! Because my mom’s co-workers took the time to talk to her about spiritual things as well as everyday things, she knew she could reach out to them. What if they hadn’t talked to her? I might not be here today. They never could have guessed that the simple conversations they had with my mom would lead to them helping to save my life.

Conversations are powerful. At Justice For All we work to equip Christians to have conversations with people around them about the important issues of our day because these conversations can have an incredible impact. Just like in my story, they can plant a seed and later maybe even save a life.

– Alora Tunstill, for the JFA Team